"Yad and Sefer Torah" by Rachel-Esther is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

When you scroll on your phone, what do you imagine happens to the text—or Tweets or photos—you can’t see? I imagine the material on the screen continuing straight up, forever. But the verb ‘to scroll’ suggests something else—that our Instagram and Facebook feeds are rolling up behind the tops of our phone screens once they slip out of sight and are at the same time unrolling before our eyes from an invisible reel at the bottom. It’s as if behind-the-scenes work, akin to the little people who live inside the television, is unfolding at the edges of our phones.

Scroll is my word for the week. It’s on my mind because the Jewish holiday of Purim is this Thursday, and it's a Purim tradition for the Scroll of Esther—a.k.a. Megillat Esther a.k.a. ‘the megillah’—to be read aloud in synagogues. The Scroll of Esther, or Book of Esther, is one of the Kethuvim (Writings) and is within the non-Torah part of the Jewish Bible. It tells the story of how Jews in Persia escaped extermination by Haman, the king’s angry advisor (and namesake of hamantaschen cookies), thanks to the titular Queen Esther.

I am a non-Jew learning about Judaism, and this will be my first time celebrating Purim. There are lots of things I don’t know about the holiday, such as whether the megillah is actually a separate physical scroll or whether it’s connected to other writings the way the five books of the Torah are all written on one scroll. I also don’t know how long it takes to read ‘the whole megillah’ (Purim is where that expression comes from). But what I have learned and can report here is that the word megillah means scroll in Hebrew.

The Hebrew root of megillah means ‘to roll,’ according to Wiktionary, which in turn cites the biblical lexicon Strong’s Concordance. This seems quite appropriate for a scroll, a document through which you move by rolling up the part you’ve just read and unrolling what’s to come. So it is for the English word scroll, which has ‘roll’ contained within it. The origins of the English word—from Old French escroe, “scrap, roll of parchment,” according to the Online Etymological Dictionary—are not particularly enlightening, except for this one tidbit: “Sense of ‘show a few lines at a time" (on a computer or TV screen) first recorded 1981.’” 1981!—the year the first IBM personal computer came out, according to this Live Science article, but decades before the iPhone.

Before I ever attended a Torah service, which is something I’ve only ever done online, I imagined a scroll as something a courtly figure would unroll vertically, like a roll of toilet paper, and that if the document were too long, the end would drag on the ground. I was surprised, then, to learn that a Torah scroll has two rollers, one at each end, and that what you’re reading is between them. You don’t read down a Torah scroll the way I’d imagined a courtier reading a scroll from top to bottom (or the way you read your phone). To be more precise, you don’t read the Torah scroll in the direction of its scrolling. Instead, you read in columns across it, columns perpendicular to the way it rolls and unrolls.

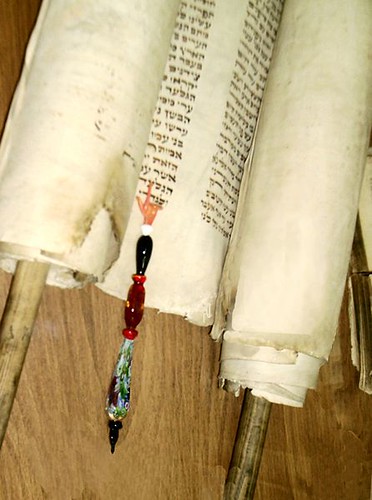

Like on a phone, though, the viewing area of a Torah scroll is always roughly the same size, limited, I guess, by the size of the bimah, the platform from which it is read in the synagogue. Another similarity between reading a Torah scroll and scrolling on a phone is the role of the finger. On the phone, you flick the feed along with your index finger. You keep your place on a Torah scroll with a miniature hand on a stick, called a yad, which has its own miniature pointer finger extended.

Of course you can read the Torah, or the Book of Esther, on your phone. In that case, then, the verb ‘scroll’ is particularly appropriate.

No comments:

Post a Comment