Tuesday, February 23, 2021

Etymological Adventures: On Scrolls and Scrolling

Sunday, February 14, 2021

Etymological Adventures: Doff and don

This week, I was writing an article about a shoe designed to be easy to put on and take off. Ah, the frustration of writing that phrase, to put on and take off. I wanted to shorten it: put on and off, take on and off. But you don't 'put off' or 'take on' your shoes unless you're in some sort of argument or fight, with your footwear. What I really wanted to write was that this shoe is 'easy to doff and don.' But some readers might not understand me if I wrote that, and I wasn't willing to sacrifice clarity for brevity (if making the piece two words shorter can be considered real progress toward brevity). So let's go on and on about doff and don in a separate article!

Doff and don do indeed mean to take off and to put on, respectively. They are contractions of 'do off' and 'do on,' according to Chambers Etymological Dictionary. 'Do' once had the meaning 'to put or place,' it seems. The Shorter O lists 'put or place' as the first meaning of 'do.' It then goes on to say that this meaning is "obs. exc. dial., with preps. (see do off etc. below)." I think the Shorter O would do well to pay a bit more attention to clarity, here. Expanding the abbreviations, the Shorter O is saying that the put or place meaning of do is obsolete except for dialect-related uses with prepositions. Prepositions such as off and on!

Memorizing the prepositions was something many students of my generation did at some point. I did that exercise in the 8th grade. A preposition, we learned, is something a squirrel could do to a tree. Well, not exactly. The squirrel goes _____ the tree, the blank being the preposition. The squirrel goes around the tree. The squirrel goes up the tree. The squirrel [tries to go] through the tree. As I contemplated writing this post, I of course wondered what other 'do + preposition' constructions might be out there waiting to be discovered. For ease of contraction, the prepositions would need to start with vowels. There aren't many exciting options. Maybe we could start using 'dup' as a contraction of 'do up,' as in 'I dupped my hair because it was hot.' Or 'dover' could mean 'do over.'

It turns out that 'dup' is already a word, albeit an archaic one. This contraction of 'do up' means to open, according to the Shorter O. Let's see that squirrel try to dup the tree. Dover is also a word. According to the Shorter O, to dover means to "doze or be unconscious" or to cause to doze or be unconscious. Or to "wander aimlessly or confusedly; walk unsteadily." Dover can also mean, as a noun, "a light or fitful sleep; a doze," according to the Shorter O. Dover's powder, the next entry in the Shorter O, is "a mixture of opium and ipecacuanha." You might think it would be used to dover people, that is, put them to sleep, especially given the opium content, but no. It was named after physician Thomas Dover. According to the definition in the Shorter O, Dover's powder was used to ease pain. Or induce sweating. I don't think the tree will be in need of dovering from the squirrel. For now, I will give the squirrel a break and sign off.

Sunday, February 7, 2021

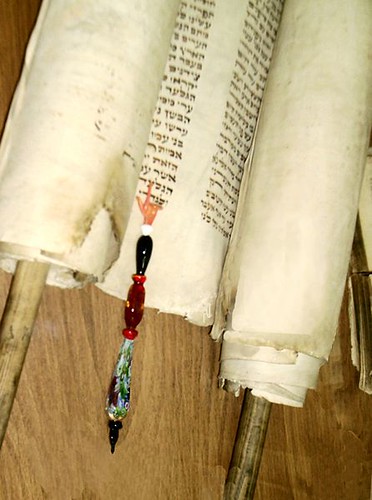

Etymological Adventures: Biblio- and Beyond

Bibliophile. Bibliography. Of all word roots, I'd say that biblio-, meaning book, is one of the most basic, for me, anyway. I feel like I've known what it meant for a long time. Why, then, did it take 36 years for me to notice that the word Bible might potentially have the very same root? That's not an interesting question, but the connection between Bible and biblio, on the other hand, is very cool.

Yes, these words all have the same root. Merriam-Webster gives me a game-of-telephone-like history of the word bible (Middle English from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek) that goes all the way back to the Greek byblos, meaning papyrus, or book. Byblos, in turn, was the name of an ancient city that exported papyrus.

When the connection between Bible and biblio hit me, it reminded me of something I read in The Broken Estate: Essays on Literature and Belief, by literary critic James Wood. Wood describes the belief, indeed still held by many people, that the Bible was a God-given account of the history of the world, the absolute truth. He calls this idea the old estate, and in his book, particularly in the introductory essay "The Freedom of Not Quite" and in the title essay, Wood describes how novels broke the old estate, or cracked it, anyway. When the Bible was considered truth, it perhaps didn't occur to people that books could be anything other than true. Novels, Wood says--and particularly novels about religious figures--changed that. All of a sudden there were these books that felt as true or truer than the Bible, yet they were entirely made up by ordinary people. Was the Bible made up, too? The existence of novels made people wonder.

It's as if, it seems to me, book originally meant the word of God as recorded by prophets. Maybe, at one time, book was a sufficient description for a religion's foundational, even holy, text. Once regular people started writing books that were patently fictional, it became necessary to find words to distinguish The Book from others. At the same time, as Wood points out in "The Freedom of Not Quite," many people also had and still have reverence for fiction, further complicating the task of distinguishing what's holy and what's not. "At the high point of the novel's rise, the Gospels began to be read, by both writers and theologians, as a set of fictional tales--as a kind of novel. Simultaneously, fiction became an almost religious activity (though not of course with religion's former truth-value, for this was no longer quite believed in)," Wood writes.

Other books do have other names: novel, memoir, stories, essays. Nonfiction is defined relative to fiction, almost as if fiction is the default. We don't have, for example, books categorized as truth and untruth. Yet the Bible, if you think about its derivation, is still basically called The Book.

PS: Chambers Etymological Dictionary says that in addition to book, the root biblio- can refer to the Bible, "as in bibliolatry = excessive reverence for the Bible." So there you go.