In the year since I’ve started exploring Judaism, my pronouns have for the first time begun to feel complicated.

The question for me is not gender identity and whether to use ‘he,’ ‘she,’ ‘they,’ or another third-person pronoun.

Religious identity is the complication.

When I write about Jews, is the pronoun ‘we’ or ‘they’?

I’m not Jewish, so you’d think the answer would be simple,

but it doesn’t feel that way at all.

In the Passover haggadah, when children ask the four questions, the ‘wicked child’ asks 'what does this ritual mean to you?'

What makes him wicked is that he uses the pronoun 'you' rather than 'we,' as if he isn’t also Jewish.

I don’t want to other the Jews. I want to be one of them.

One of us?

It gets particularly complicated when I’m writing about what Jews do, or what some Jews do, from my recent experience of doing the thing,

like reciting a list of communal sins and trying to atone for them on Yom Kippur.

It was in a blog post that related to sin and Yom Kippur traditions that I had to make a decision whether to write ‘we’ or ‘they’ to refer to Jews.

I chose ‘we’

because I wanted to.

Yes, it was in part because I didn’t want to other the Jews,

but it was mostly because I wanted to be part of the group.

If I had to choose—and I did, pronouns-wise—I chose the Jewish people.

Another way to look at it is to say that I was referring not to Jews but to people who observe Yom Kippur.

Although not yet a Jew, I had recently become a ‘person who observes Jewish holidays.’

I wanted to write 'we' to indicate that I was speaking from experience (although just one Yom Kippur’s worth, to be fair) and not writing about something other people do.

To imply that observing the High Holy Days was something Jews did and I didn't would be inaccurate

and would also raise the questions: Why am I talking about this, then, or how do I know this?

Writing ‘we’ also has the potential to be wicked, though, because it could give the impression that I'm Jewish, when I'm not

yet.

I need an in-between pronoun, a pronoun for someone who isn’t Jewish but who does Jewish things.

We/they

How about 'whey'?

In a writing workshop, I marveled at a person who, during introductions, specified that this person’s pronoun was ‘we.’

Now I understand

identifying as ‘we’ and wanting to express that.

If I intended to do Jewish things without becoming Jewish, I suppose I could distinguish between doing and being:

Who I am versus what I do;

Who I am and who Jews are

versus what some Jews and I—that is, we—do.

But I do intend to become Jewish. I’m converting.

Who I am is changing.

'We' is a first-person pronoun used to refer to oneself and others in the same group. It requires knowledge of oneself and of the group.

Am I in a group with these people?

Answer ‘yes’ and the pronoun is ‘we.’

Am I separate from these people?

Answer ‘yes’ and the pronouns are ‘you’ and ‘they.’

But what if you answer 'sort of'?

If I ever thought there was anything simple about the pronoun ‘we,’ I renounce it.

The question: ‘What are your pronouns?’ deals mostly with what others call you, the third person.

But this is about the first person; this is about what I call myself.

Comment m'appelle-je?

What is my name?

Others can't answer the question for me.

But then again, they can and do. It's as simple as 'let's go!'

It's as simple as 'and we say amen.'

I am turning Jewish, converting.

I’m somewhere in between,

outside of the binary, Jew or non-Jew.

I'm not Jewish, but…

I'm not Jewish, yet.

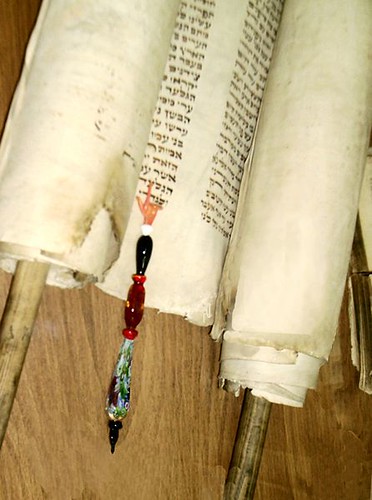

Abraham was the first Hebrew, and Hebrew, or Ivri, in Hebrew, comes from a verb that means to cross over.

Transition comes from the Latin trans (across) and ire (to go).

I am transitioning to a Hebrew identity

(and by Hebrew I just mean Jewish).

Is the act of transition inherently Jewish?

I'd like to think so because it makes me feel as if my converting were somehow meant to be,

that I've put the etymological key in its lock and opened a door, to Judaism, that was waiting for me.

I'm not entirely sure what Abraham crossed over.

The Israelites crossed the Red Sea, and the Jordan.

I think that Abraham crossed over in a religious sense.

He rejected his father and his father’s religion, smashing the idols in his father’s shop, to follow God and God's instructions.

He also left his first home

in search of a new one.

"Go forth from your native land and from your father's house to the land that I will show you," (Gen. 12:1) God told Abraham.

I know, or have some idea, where I’m going,

who I’m becoming,

where/who:

Israel.

I wear the star around my neck

alongside a pendant the shape of Mount Desert Island, Maine, where I grew up.

I was raised ‘not Christian’ by parents who rejected the religions of their childhoods.

How Jewish of them, how like Abraham, except that they also rejected the notion of God.

My mom taught me not use 'God' as an exclamation,

but this was out of respect not for the Lord and commandments but for other people.

We ate challah on Christmas Eve and,

at Easter, made Ukrainian eggs (though we weren’t Ukrainian either),

drawing designs with wax, dying the eggs, melting off the wax,

and (of course my mom did all the hard stuff) very carefully blowing or sucking out the eggs' raw innards.

My mom made the challah and also “Czech Christmas Bread”

using recipes from the New York Cookbook.

What we didn’t do was go to church.

The time a babysitter taught me a bedtime prayer about dying, my dad was quite upset,

or so goes the story my mom tells; I was too little to remember.

After her husband died, the Bible’s Ruth had to make a choice between two religions and two groups of people because she had to decide where she was going to live: Moab, with her native people, or Bethlehem, with her mother-in-law Naomi and the Jews.

She couldn’t be between the groups.

As was the case for Abraham, the question of which religion to follow was tied up with that of parents and whether or not to leave them.

"Turn back, each of you to her mother's house" (Ruth 1:8) Naomi said to Ruth and to Ruth's sister-in-law.

Indeed the sister-in-law went back "to her people and her gods" (Ruth 1:15).

But Ruth continued on to Bethlehem and in so doing chose the Jews.

Instead of going back, she went across, geographically and spiritually.

Her story became a Biblical example of conversion to Judaism.

Becoming Jewish won’t change (New York!) where I live,

but in Judaism I will have a new 'spiritual home,' as the phrase goes, or maybe just new places for my spirit to venture.

I'll also get a new name, a Hebrew one.

In it, I’ll be identified as the daughter of Abraham and Sarah, as opposed to the daughter of my own parents.

How will I call myself? Ashley, daughter of Ben and Sandi

or Ruth bat Abraham v'Sarah?

It will be both.

With two names, I'll be a ‘we’ all on my own.

But I’m not

on my own.

This year, during my first breadless Passover,

at my parents' house,

I assembled Seder plates and my mom made macaroons dipped in dark chocolate

—my dad is certainly pro-macaroon—

which we all ate.

Note: This piece records how I felt as early as June, 2021, when I first submitted the piece for discussion in my writing group. As time has passed, I've felt more and more like part of the group at my synagogue and beyond. I wouldn't have sat down and written this piece today because I no longer feel like an outsider hoping to be let in. Wait another week and I'll have to change 'one Yom Kippur's worth' to 'two' because I will have observed the High Holy Days for another year. So this piece is a time capsule from mid-conversion. Many pieces of writing are time capsules by the time they are published. It's quite likely that the next time I publish anything else about religion, I will be Jewish.